The $20 Million Gold Offer—and the Hidden Tax Behind Inflation

How a “legal” gold scam reveals who gets the new money first—and why gold still measures trust in fiat systems.

Recently, I listened to an episode of Tucker Carlson’s podcast titled One of America’s Biggest Gold Wholesalers Exposes the Most Common Gold Scam Enslaving the Country.

The guest, Christopher Olson, one of the largest gold wholesalers in the United States, speaks with striking candor about a disturbing reality: a significant portion of American retirement savings is being quietly eroded by what is, in many cases, a perfectly legal gold scam.

This podcast goes far beyond gold itself. Gold is used as a lens to examine much larger questions about the modern financial system. It prompted me to reflect more broadly on gold and silver, precious metals and commodities, minerals and mining, inflation, Bitcoin, the fiat currency system, and the role of the Federal Reserve.

The conversation begins with an unusual anecdote. Tucker recalls that a gold company once offered him $20 million to promote their gold products. The offer felt inherently suspicious. Gold is a commodity—its price is set by global markets. Why would anyone need to pay such an extraordinary marketing fee to sell gold?

The answer, Olson explains, is simple: it isn’t really about gold. These companies sell “commemorative” or “collectible” coins at prices often double the underlying value of the gold itself, marketing them as safe, retirement-friendly investments. The product is legal, the markup is hidden, and the cost is borne almost entirely by unsuspecting retirees.

Inflation as a Distribution Story

What struck me is that this kind of “legal scam” isn’t just a story about gold marketing. It reflects a deeper mechanism that shows up everywhere in the modern financial system: inflation is often less about prices rising, and more about who gets the new money first.

Olson frames it in a way I found unusually clear. When new money enters an economy, the earliest recipients—those closest to the source of issuance—can spend it before the rest of society has adjusted its expectations. The market hasn’t yet received the “signal” that there is excess money in circulation, so prices don’t immediately change. In that window, early recipients effectively gain purchasing power that others don’t. That gap—quiet, uneven, and hard to see in real time—is where inflation’s most consequential effects often come from.

He illustrates it with a simple thought experiment. Imagine everyone living on a small desert island with a stable economy and relatively stable prices. Overnight, a magical event doubles the amount of money in everyone’s bank account—evenly, for everyone. If everyone understood this collectively, they’d immediately realize that the prices of everything should also double. Doubling money doesn’t double goods, services, or real wealth—it only doubles the claims on that wealth. In that scenario, no one truly gains an advantage, because everyone’s purchasing power changes at the same rate.

Now change one detail: instead of everyone receiving new money, only a small group does. Prices won’t instantly adjust, because the broader market can’t detect what just happened. The new money enters quietly through a narrow channel, and the people who receive it first can buy real goods and services as if nothing changed—while everyone else discovers the consequences later, through higher prices and a weaker currency. Olson describes it as a kind of “hack”: allowing some participants to acquire claims on real wealth that they didn’t earn, simply because they were positioned closer to the point of money creation.

That’s why this isn’t just a macroeconomic theory—it’s a distribution story. And it’s also why he makes a remark: gold is the original “cryptocurrency.” Not because it’s digital, but because it is hard to manufacture, difficult to counterfeit, and resistant to arbitrary expansion. In a world where money can be created by fiat, the appeal of “hard money”—whether gold, or today’s Bitcoin—starts to make psychological and financial sense.

Where Does Gold Come From?

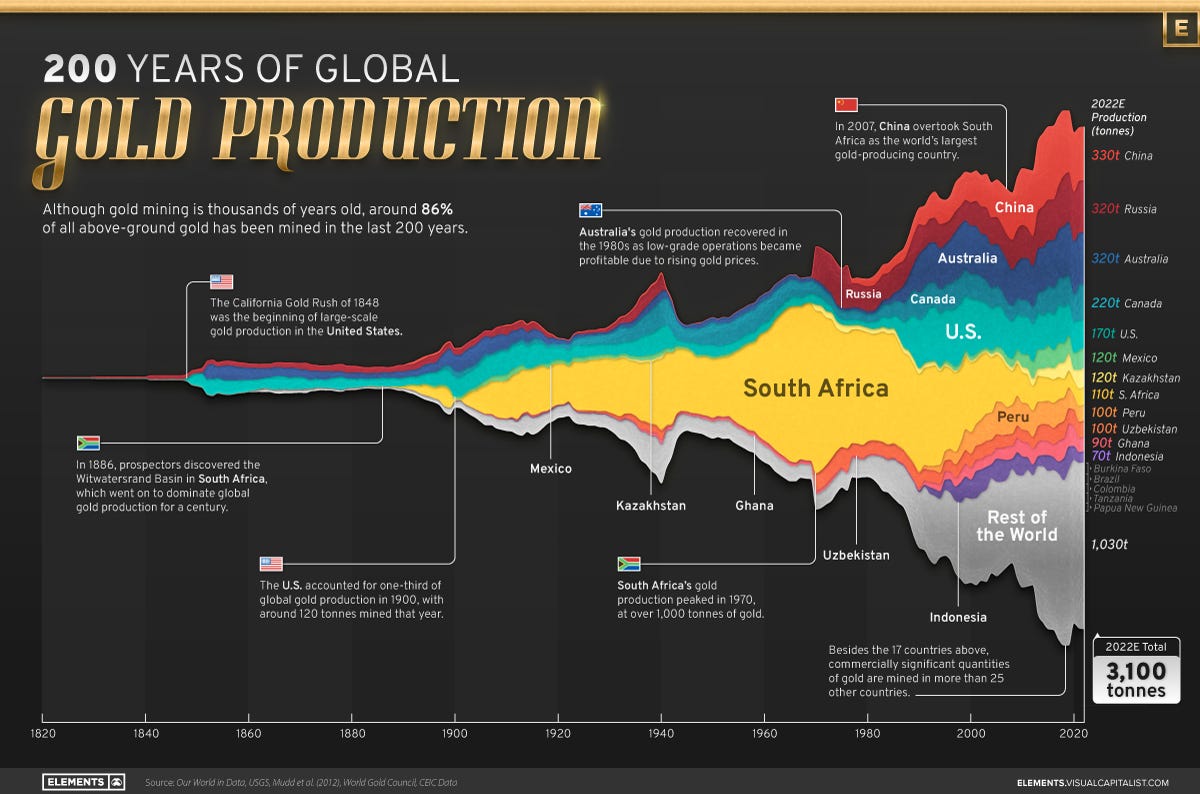

If inflation is a story about distribution—who gets purchasing power first—then it’s easier to see why people keep returning to gold. But before treating gold as an abstract hedge, it’s worth grounding it in something simple: gold is a physical commodity with a real supply chain. It is mined, refined, standardized, vaulted, and traded through a few highly concentrated channels.

On the market side, price discovery tends to cluster around a handful of hubs. In the U.S., COMEX (CME Group) in New York anchors much of the futures market. In Europe, the wholesale physical market is organized around the London Bullion Market Association (LBMA)—a standards-and-settlement network best known for “good delivery” bars. In Asia, the Shanghai Gold Exchange plays a comparable role.

On the supply side, newly mined gold is only part of the picture. Annual mining output expands total above-ground supply by roughly 1–2%, but most gold already exists—and it doesn’t disappear, it circulates. A large share of supply comes from existing holdings being sold, recycled, or reallocated through the secondary market.

This is where refineries matter. Refineries bridge the messy physical world and the standardized financial one: they take dore from mines and scrap from the secondary market, and convert it into trusted, tradable bars that meet institutional specifications. In practice, refineries don’t just process metal—they turn physical gold into financial-grade gold.

So when people say they’re “buying gold,” they’re not only buying a metal. They’re buying into a system of extraction, standardization, custody, and market structure—a physical network that sits quietly underneath modern finance.

Fiat Money, the Federal Reserve, and the Hidden Tax

Gold’s supply chain is slow, physical, and constrained. Fiat money is the opposite: it can be expanded by policy, routed through institutions, and injected into the economy through narrow channels.

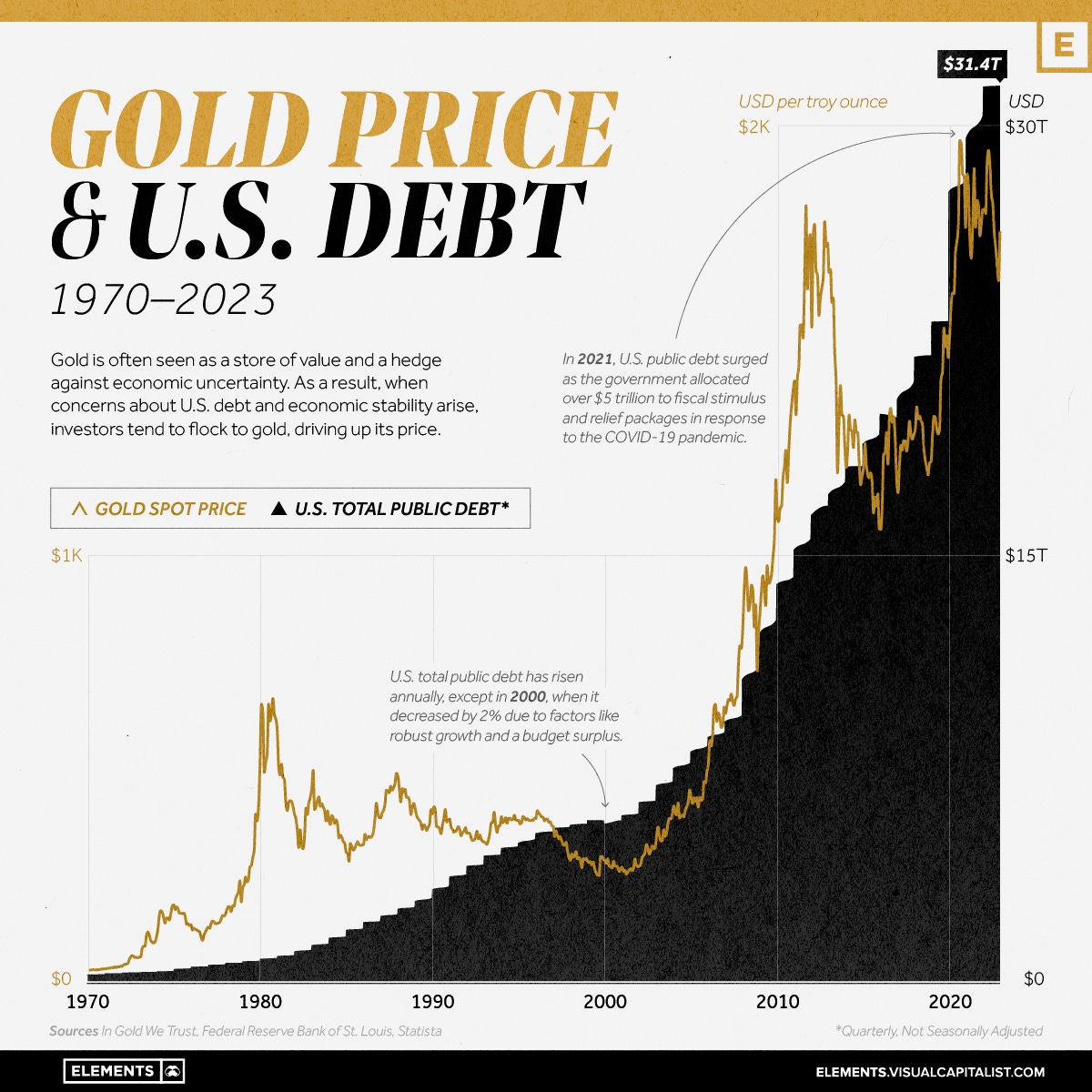

Olson argues that the ability to create artificial credit or money concentrates power in the hands of a relatively small set of actors: central banks, primary dealers, and the institutions closest to issuance. When governments can finance themselves by expanding credit and monetizing debt, they don’t always have to ask citizens to pay directly through visible taxation. Instead, they can impose something quieter: a hidden tax on everyone who holds the currency.

And because the U.S. dollar is not just America’s currency but a global one, that hidden tax doesn’t stop at U.S. borders. It is effectively spread across households, businesses, and governments worldwide—anyone whose savings or reserves are held in dollars.

This is why the gold standard still matters in these conversations—not as nostalgia, but as a concept of constraint. Under the post–World War II system, the dollar was pegged to a fixed amount of gold, giving holders of dollars a clearer accounting of what a “dollar” was supposed to represent. The discipline wasn’t perfect, but the principle was simple: money creation had a hard reference point outside politics.

Once that constraint is removed, money becomes more elastic—and so does state capacity. The modern world has gained flexibility, but it has also normalized a system where purchasing power can be diluted without an explicit vote.

In that light, gold’s role becomes clearer. Gold doesn’t “solve” the fiat system. But it does something uniquely uncomfortable: it measures. It acts as a barometer of confidence, a check on narratives, and a reminder that not all forms of money are created—or expanded—equally.

Conclusion

Taken on its own, the “commemorative coin” scam looks like a niche story—just another case of aggressive marketing and opaque markups. But the longer I sat with the episode, the more it felt like a microcosm of something larger.

At its core, the scam works because of asymmetry: one side understands pricing, liquidity, and incentives; the other doesn’t. Inflation often works the same way—not merely as rising prices, but as a quiet transfer of purchasing power to those closest to money creation. And gold, for all the mythology around it, is ultimately just the opposite of that: a hard, physical asset with real constraints, moving through a real supply chain, priced through a concentrated market structure.

Gold doesn’t fix the fiat system. Bitcoin doesn’t either. But both attract attention for the same reason: when trust in institutions weakens, people look for forms of money that feel harder to bend—assets with clearer rules, clearer limits, and fewer hidden levers.

If there’s one lesson I’m taking from Olson’s story, it’s not “buy gold.” It’s simpler—and more uncomfortable: in finance, what matters most is not the label on the product, but who controls the pricing, who controls the channel, and who bears the hidden costs. That’s true for collectible coins, for inflation, and for the monetary system itself.