Andrew Carnegie: How a Young Man Learns to Stand in the Tide of History

Podcast Notes — Reflections on History, Society, Culture, Humanities, Life, and Work

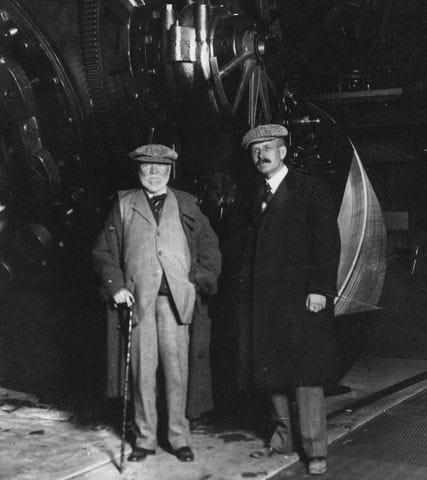

Recently I listened to the podcast “Andrew Carnegie” by Ben Wilson, which describes the rise of Andrew Carnegie from a poor Scottish weaver’s boy to an American millionaire.

The episode is based on two books:

Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie by David Nasaw

I have loved reading biographies since I was a kid, and this was the first time in a long while that I experienced one through a podcast instead of a book. As I listened, I took notes — fragments of ideas, turning points, sentences that stayed with me — and I wanted to shape those notes into this essay.

For me, Carnegie’s life is not merely the story of a poor Scottish boy becoming a millionaire. It is a study in how a young mind observes the world, responds to change, and learns to find a place inside forces larger than himself.

Hearing about the world he lived in, the experiences he had, and the decisions he made, I found myself reflecting on all kinds of things — history, society, culture, the humanities, life, and work.

I’m going to divide Carnegie’s life into two phases, using his investment in Adams Express as the turning point. It was the first moment he entered the world of capital, and it changed the trajectory of his life.

So in this essay, I’ll walk through both phases — what he experienced, what he chose, and what those moments made me think about.

From Childhood to Becoming Thomas A. Scott’s Right Hand

Carnegie’s story begins with a disruption. When he was young, the mechanical loom arrived and wiped out his family’s weaving trade. The first Industrial Revolution brought enormous growth, but it also displaced countless families — including the Carnegies.

It made me think about today. Nearly two hundred years later, what will AI or quantum computing do to our existing social structures? Will they reshape jobs, industries, and families the same way the mechanical loom reshaped Carnegie’s world?

After his father lost work, the Carnegies looked around Scotland and saw no path forward. So they made the bold decision to immigrate to the United States. In Carnegie’s early years, I could see the outlines of many immigrant stories — including echoes of my own. How a young outsider adapts to a foreign culture, learns its rules, survives its uncertainty, and slowly finds a place to stand.

Three humble jobs — but not a humble mindset

In America, Carnegie worked three extremely humble jobs: bobbin boy, messenger boy, and telegraph operator. But he approached these jobs very differently from the people around him. He wasn’t just working to earn a wage — he was studying, absorbing, preparing for a future he couldn’t yet name.

He treated small jobs as foundations for a larger future.

Two small stories that reveal his character

1. The messenger-boy interview

During his interview for the messenger job, he was hired on the spot — and he started work immediately. His uncle, who referred him, was still waiting outside, unaware that Carnegie had already begun his first shift.

Carnegie later wrote: “I think that answer might well be pondered by young men. It is a great mistake not to seize the opportunity.”

From this, I realized how he approached uncertainty: move quickly, reduce randomness, and avoid letting unpredictable factors block your path.

He never assumed time was on his side.

2. Remembering names

As a messenger boy, he memorized the names and faces of every businessman he met.

I’ve been reading Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People recently, and there’s a chapter devoted to this exact idea: the importance of remembering names.

It’s a small detail, but small details often reveal about a person’s orientation.

Investing in himself outside of work

He joined debating societies and practiced public speaking. He discussed religion and politics with friends in Henry Phipps’s cobbler’s shop. All of these activities looked “unprofitable” on the surface, but they later became his most important abilities: persuasion, negotiation, relationship building, writing and staying composed in public.

The self-improvement you do when you’re young isn’t for the present—

it’s for some unknown position your future self may one day be asked to step into.

Becoming Thomas A. Scott’s assistant

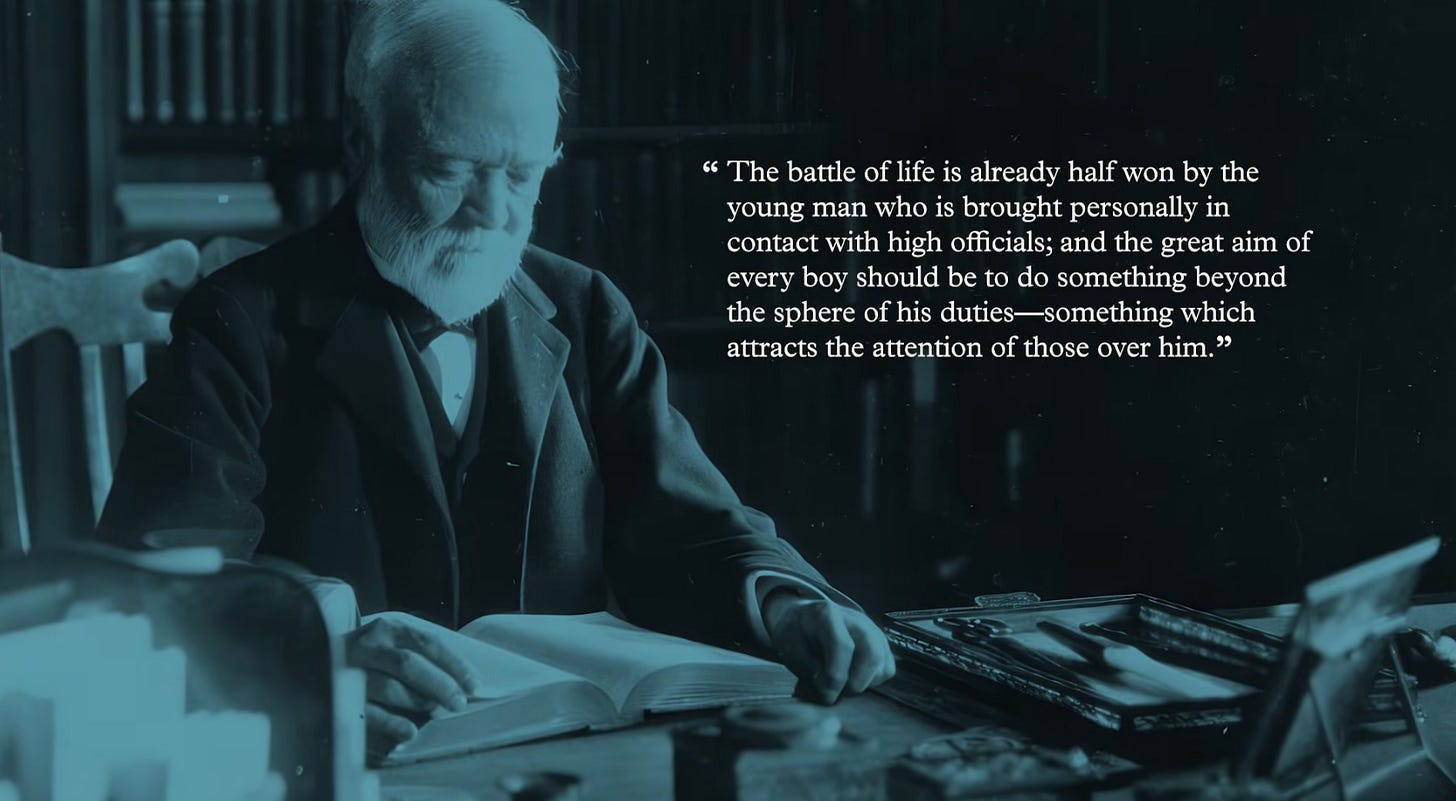

Eventually, he caught the attention of Thomas A. Scott from the Pennsylvania Railroad. Carnegie took initiative, did things far beyond his job description, and earned Scott’s trust.

He later wrote: “The battle of life is already half won by the young man who is brought personally in contact with high officials; and the great aim of every boy should be to do something beyond the sphere of his duties—something which attracts the attention of those over him..”

By this point, he had already built a remarkably solid early career — not by luck, but by how he moved through the world.

Adams Express — His First Steps Into Capital and Ownership

One day, Scott asked if he wanted to invest in a new venture: Adams Express.

Carnegie mortgaged his family’s home and said yes. This was his first experience with capital returns, and it sparked a new line of thinking for him:

What does it mean to own something?

How does money create more money?

This was the true beginning of his life as a capitalist.

Entering new industries early

He stayed alert to emerging industries. When the oil industry was just beginning, he invested in Columbia Oil.

This reminded me to stay alert as new breakthroughs like AI and quantum computing emerge — to be sensitive to information and early signals.

Choosing ownership

At 29, Carnegie resigned from the railroad to focus on ventures he actually owned. He entered iron production and private bridge-building, relying on the relationships he had built over the years — especially within the railroad companies.

This shift was not just a career change. It was a change in identity: from worker to owner.

He did many things at once

He became a financial middleman for industrialists and bankers. He was a natural marketer, quick to understand trends. He built networks, hosted dinners, formed partnerships, and constantly absorbed industry information.

He didn’t just work — he positioned himself at the center of information, relationships, and opportunity.

Conclusion

From Carnegie’s story, I saw how a young man can start with almost nothing and still find a path toward something larger — not by luck, but by how he chose to see the world, how he positioned himself, and how he responded to the opportunities that appeared.

When I look back at the factors that shaped his rise, many of them are not tied to his era. They are patterns that remain true today, and patterns that I find relevant to my own life as well:

Choose the right circles and environments.

The city you live in, the industry you enter, and the people you surround yourself with matter more than we admit.

Learn from people who are older, better, and more experienced.

Being around those who have already walked further pulls you upward.

Have the courage to take risks.

Avoiding risk is often the biggest risk of all.

Don’t let opportunities wait.

When something opens, act quickly and do your best — hesitation creates uncertainty.

Don’t work just to work; work to learn.

Every job is a chance to grow, to build skills, and to position yourself for what comes next.

Stay alert to new industries and new technologies.

Enter early, stay curious, and keep your information senses sharp.

Build the ability to gather information and build relationships.

Becoming someone who can connect people, read situations, and communicate with ease is its own kind of advantage.

These principles don’t guarantee success, but they shape the possibilities available to us.

And that, more than the wealth Carnegie eventually gained, is what makes his story worth learning from today.